The Burning Bus

McClain: “Man, you don’t know what it was like, in this town.”

Rev. Bob McClain, a native of nearby Gadsden, had just been named pastor of Anniston’s Haven Chapel United Methodist Church. He was 24 years old, newly married, fresh out of seminary in Boston, and was committed to changing Anniston’s oppressive racial climate.

McClain: “I expected the Methodist preachers to welcome me with open arms. They wouldn’t even talk to me on the telephone, let alone come to the office.”

After striking out with the Methodists, McClain telephoned all of the city’s white Baptist pastors with the same result. Somehow, he got the name of Rev. J. Phillips Noble, pastor of Anniston’s First Presbyterian Church.

Noble: “The whole thing of what was happening during the Sixties was an absolute absurdity. And of course, it had been an absurdity for years. It was an emotional time, from the standpoint that so many terrible things were happening in the South. I knew it was wrong, but I wasn’t really doing anything, you see?”

From the beginning, McClain and Noble was the most unlikely of partnerships…a young black firebrand, and a middle-aged, white, soft-spoken moderate, born and raised on a farm in Mississippi. But somehow, the two hit it off.

This past weekend, McClain and Noble were reunited for the first time in 40 years…at a civil rights symposium hosted by the Anniston Public Library, to celebrate the publication of Noble’s new memoir, Beyond the Burning Bus, from NewSouth Books in Montgomery. The title refers to one of the darkest headlines of Anniston’s history, when members of the Ku Klux Klan ambushed a busload of Freedom Riders in 1962. Noble’s book also contains the untold story of the dramatic events in Anniston on September 15, 1963, that would forever be overshadowed by Birmingham’s tragedy.

As McClain says, in the preface he wrote for Noble’s book, he remembers vividly the day that he and fellow black pastor Nimrod Reynolds, of Anniston’s 17th Street Baptist Church, first met with Noble…

McClain: “I remember the day very well. I can almost feel Nimrod’s car, and us driving literally across town. Anniston was divided, really. We said, we’ll just tell him the way it is, how black people feel…and lay it out before him and see if he was a Christian. That was the way we approached it… ‘See if he was a Christian.’ He was gracious. He seemed a little shaky at first, but gracious. We talked about no jobs, discrimination, segregation, colored restrooms and waiting rooms.”

Noble: “And when they said what I already knew…the burden of segregation, and the dehumanization of discrimination that was taking place…to say that, and to hear them say that, it was moving. It was moving.”

McClain: “Nimrod talked, I talked. We looked up and Phil said, ‘Brothers, let’s pray.’ I will never forget him…(voice breaks)”

Even today, McClain’s eyes fill with tears when he recalls the breakthrough of that first meeting.

McClain: “By the time Phil asked the Lord to be present with us and to help us figure out what to do, tears were coming out my eyes, and Nimrod’s eyes, and we looked up and Phil was crying. I had never seen a white man cry about black folks before.”

All three men would soon become members of the Human Relations Council, with Phil Noble as its chairman. Fast-forward to September 15, when McClain and Reynolds were chosen to drive downtown that afternoon and de-segregate the city’s main library.

McClain: “I remember our discussion…do you, Phil? We said, ‘This will be the easiest.’ (Laughs)”

Noble: “Yes, I do. (Both men laugh hard.)”

McClain: “Realize what we’re talking about. We’ve just heard this morning that 16th Street Baptist Church has been bombed, and four little girls, black girls, have been killed. In Birmingham, which is 60 miles away. We’ve just heard that. You have to remember what that…what it… (voice trails off)”

Noble: “We were going to see that the library was integrated, to say to two groups…to the whole community wide, and especially to the hoodlums, the city is going to run itself, and the hoodlums are not going to determine what happens, what we do, in this city.”

McClain: “As I remember it, there were steps up to the library from the street, I believe, and then a landing, and then some more steps. When we got up to the landing, I looked and I saw a lot of people. And that was unusual, because it was a Sunday afternoon and you didn’t expect much activity. From every direction, there were men, white men, coming at us. I could see them coming from cars, from back of the library, from every direction. The newspaper said there were 75 of them. I don’t know how many there were. It looked like thousands and thousands, to me. (Both men laugh) We never made the second set of steps.”

Noble: “Chains, and knives, and clubs.”

McClain: “‘Niggers, niggers, niggers.’ That kind of just…hate stuff.”

Reynolds was the first to hit the concrete, bleeding badly. McClain was able to ward off the blows long enough to drag him back to their car.

McClain: “They had jammed the car in so closely I couldn’t get the car out…”

Noble: “There was a shot fired.”

Phil Noble was not at the library that day, but he’s heard the story so many times that he spontaneously fills in the gaps…

Noble: “A shot came through the glass of the automobile. It landed in the seat right behind…”

McClain: “Right behind my neck. So we got out of the car and I literally carried Nimrod as we ran down the street. I don’t know how we got out of there, to tell you the truth. I really don’t know why and how Nimrod and I are alive.”

Noble: “It’s providence. God’s providence.”

As word of the pastors’ beatings spread throughout the city, people from the black community began gathering at Rev. Reynolds’ church…a crowd of hundreds, that soon grew to more than a thousand. Reynolds was in bed from his injuries, so the task of speaking to the angry crowd fell to McClain.

McClain: “There were more people outside 17th Street Baptist than there were inside. And the people came with guns and knives and everything else. They were ready to come and rip this town apart. I preached from Isaiah… ‘He was wounded for our transgressions, He was bruised for our iniquities. The chastisement of our peace was upon Him, and with His stripes we are healed.’ I urged them, that night, not to go into town. ‘We know you’ve got the guns, we know you’ve got the power. Please, brothers and sisters, we’re not going to turn into violent people. We’re Christians.’ And that was the only thing I had to use was the gospel as I understood it. (Pause) They heard. They heard.”

Noble: “I’ve said so many times, that white people ought to be so grateful that the leaders of the civil rights revolution were ministers, like Martin Luther King, and Bob, and Nimrod, and us. You could have had other kinds of people leading it who would have had bloodbaths all over…you see what I’m saying?”

McClain: “Although Anniston would face its share of racial struggles in the months to come, there was a widespread feeling that the city had somehow turned a corner, that night. Even today, McClain says, as he travels the country, preaching and lecturing, people sometimes come up to him afterward, to talk about that long-ago Sunday.”

Noble: “On occasion, someone will come up to me and say, ‘You know, I’m from Anniston, Alabama. I’m ashamed of what happened to you and Rev. Reynolds.’ I say… ‘We did what we had to do. I hope you are now working at changing things like that, wherever you are.’ And I believe that. I believe if you’re serious about being a Christian…serious about being an American…you ought to be working at making sure people are treated right. I’m not talking about Iraq. I’m talking here in the United States. We ought to make sure that everybody has freedom and liberty, and nobody’s discriminated against. This is a great country, but it can go down, too.”

McClain: “Yeah.”

Birmingham is 3rd worst in the Southeast for ozone pollution, new report says

The American Lung Association's "State of the Air" report shows some metro areas in the Gulf States continue to have poor air quality.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

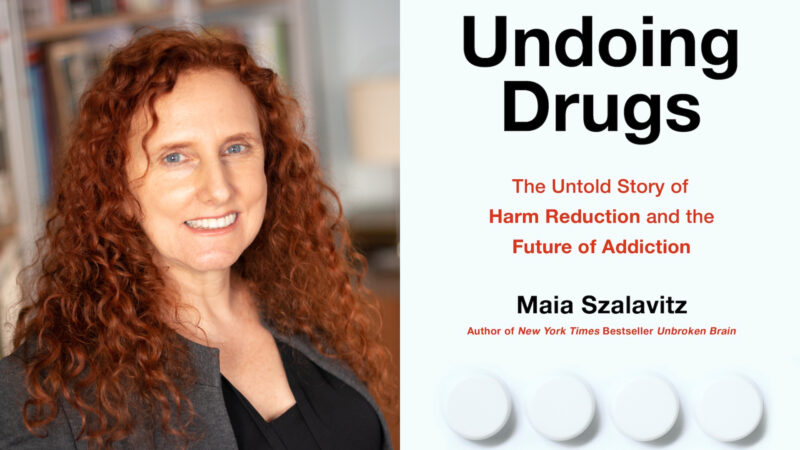

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.