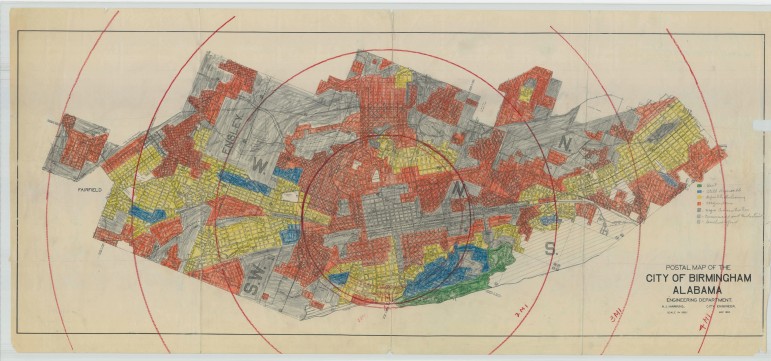

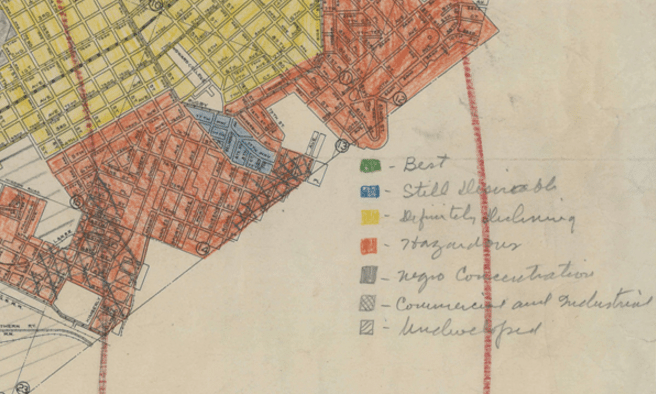

Commentary: Not Easy to Find “Home” with Birmingham’s Redlining History

In the 1930’s, the Federal Housing Authority practiced “redlining,” denying services to people in certain areas based on racial or ethnic makeup. This mostly discriminated against black, inner city neighborhoods. In Alabama, Birmingham was no exception. The echoes of redlining can still be heard today, especially when young black families start house shopping. In this commentary, young adult author and WBHM staffer Randi Revill shares her thoughts on searching for home among Birmingham’s silent but ongoing racial division. Revill’s first novel, “Into White,” comes out this Fall.

As a child, I loved visiting my grandparents. Their tiny red and white house stood in the heart of Smithfield, near Elyton Meat Center just over the Center Street railroad tracks. I could get lost in my grandfather’s tales of W.C. Handy and other blues musicians while devouring my grandmother’s ambrosia, but even as a child, I wondered why they chose to live in racially segregated Smithfield. When I discovered redlining, I began to understand that they didn’t choose Smithfield. Smithfield was chosen for them.

In the 1930s, Birmingham’s officials sliced out neighborhoods for black families, funneling them into approved areas. In those redlined communities, the budget for community aesthetics was slashed, leaving roads unpaved and yards overgrown. Meanwhile, the Birmingham suburbs, affectionately referred to as Over the Mountain, raised in status and value.

For years, I toiled with the thought of my sweet grandparents being stripped of the freedom to choose where they could lay their heads, but it’s hard to know what to do with those feelings. Those officials are long dead, and I’m free to live wherever I want. So I filed redlining alongside other injustices my ancestors endured, and decided to move forward. That is, until my husband and I began searching for a neighborhood of our own.

In search of the perfect community, I went on GPS-free, self-guided, neighborhood-hops around Birmingham. I’d start near Eastlake Park, and ride 1st Avenue into the heart of the city. I’d hang a right at John’s City Diner straight into the hills of North Birmingham. Then I freestyle it. Looping and looping through the Northside, and riding out Center Street until it T-boned with Green Springs Highway. Then I’d take a left by the Heritage Shopping Center which leads to the “over the mountain” communities. First Homewood, then Vestavia, then I’d get completely lost in Mountain Brook, and somehow emerge into Forest Park. Lastly, I’d cut through Avondale to get back onto 1st Avenue, and stop by East 59 for a celebratory cup of coffee.

But after a few of these tours, I realized the red line still exists in our city. In 2016, Birmingham is still deeply segregated, and as a young family seeking diversity, community, and safety, which side of the red line do we choose?

I’m frequently told to move “over the mountain” where the tree-lined sidewalks are safe and clean. That’s the obvious choice for a sweet young married couple, but I hesitate since my grandparents wouldn’t have been allowed to live there when they were a sweet young married couple. Their only access points into those homes were as maids and janitors. Some say it’s my responsibility to move back to Smithfield and help cure the problem from the inside. To heal decades of damage designed by a system created before my mother was even born.

I want to ask my grandparents what they think. Would they be disappointed if we moved back to Smithfield? Would choosing an “over the mountain” neighborhood dishonor their sacrifices? But I can’t ask them. My grandfather’s wise council and grandmother’s ambrosia only live in my memories now, but the effects of redlining are still dividing our city.

Taking a red pen to the map in the 1930s and carving concentrated areas for black families has shaped the racial landscape of the city, and many diverse young families are leaving since they don’t fit on either side of the red line.

My husband and I are still figuring it out for ourselves, but Birmingham as a whole must make an effect to stop shutting our eyes to the division, or it won’t change. I encourage every resident to tour our city – GPS free.

This commentary is part of WBHM’s “Y’all Talk” series, and was produced by Amy Sedlis. Find out more about how YOU can submit a commentary here.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.