A Hispanic Church Reflects on Immigration Reform in Alabama

After House Majority Leader Eric Cantor primary defeat last week, immigration reform is taking center stage yet again. Alabama is no stranger to the immigration debate. The state’s immigration law, HB 56, was known as the toughest in the nation when it passed in 2011. But a federal settlement last fall blocked several key provisions of the law.

For WBHM, Nathan Turner Jr. visited a local Hispanic church to explore what’s changed for the congregation since the settlement. He also hears what some say still needs to change in Alabama’s immigration policies.

Ezequiel Osorio is pastor of the 120-member Hispanic Seventh Day Adventist Church in Titusville in west Birmingham. His congregation was in Hoover in 2007 and moved to west Birmingham in the last couple of years.

“We have not had any problem with the community around the church,” Osorio says, “Most of the people have been very kind to us.”

The Guatemala native and his family have been U.S. citizens for nearly 20 years. Most of the parishioners at his churches are from Mexico and Central America. In 2011, the original Alabama immigration law forced several of his church members to leave the state. But now Osorio is encouraged that parts of the law have been blocked.

“At the beginning we were very concerned because we know that this kind of law can scare Hispanic people and of course some of them were scared and many Hispanic people left the state.”

But Osorio assured his members that they would overcome the legal issues.

“Sometimes we forget that the original members of the country were native Indians and the white people were foreign. I do not think they showed a visa when they came here or applied for immigration status,” he says.

A federal settlement approved in late 2013 struck down several sections of HB 56 that critics called “self deportation policies.” This included a provision that prevented undocumented immigrants from entering legal contracts. Another would have required students to provide legal status for public school enrollment. A third section allowed law enforcement officers to check the legal status of undocumented immigrants during traffic stops.

Osorio pastors four other churches in North Alabama. For the sake of his church members and others, he says lawmakers must be see immigration in a more spiritual light.

“We don’t have to be too hard. We have to see the human part of the law. We need compassion and mercy,” says Osorio.

Birmingham immigration lawyer Monique Okoye is more upbeat about the changes that were made in the November settlement, but she’s still cautiously optimistic.

“Right now we’ve struck down some provisions that were offensive but there are still some things that remain,” she says.

Okoye says the law still blocks undocumented immigrants from getting drivers licenses. This fact, she says, elevates the chances that a person will be deported.

“The problem is the way that the law is written,” Okoye says. “While you explicitly may not stop people in order to look at their immigration status, if you stop them for not having a drivers license and you take them to jail, then they are going to be put on an immigration hold. You essentially have the same issue.”

Okoye is especially glad the provision preventing undocumented immigrants from signing contracts was struck down. She says several of her clients had been unable to renew their business licenses under HB 56.

“We had a client who owned a Subway. He went to renew his license and was arrested and detained. He is now facing deportation,” Okoye recalls. “There have been undocumented workers who have been here 20 or 30 years and who already have flourishing businesses. They need to renew their business licenses to stay in business.”

Okoye favors federal reform to prevent a patchwork approach to the immigration issue. And she believes such reform should help the undocumented work toward citizenship and allow them to pay state taxes. She also adds that business licenses and other formal legal documents add much needed revenue to the city and the state.

At the Hispanic Seventh Day Adventist Church church, members have relaxed in the shadows of the federal settlement. Since Alabama’s immigration law has mellowed, Pastor Orzorio has seen more people at the services. Even a few that had left are returning.

Overall, he wants what he calls a more humane solution to the states immigration issues.

“In the eyes of God, every man and woman is created equal,” he says.

Ozorio says there is still much work to do to balance the scales of justice for the undocumented immigrants. He hopes any new laws will temper justice with mercy.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

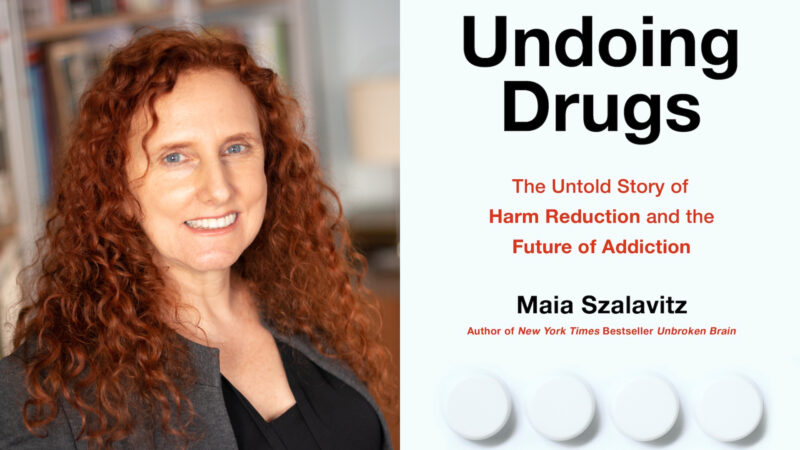

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.