The Postman’s March

While 1963 was a turbulent year for the civil rights movement in Birmingham, Gadsden was relatively calm. That is until a white man named William Moore set out on a solo protest walk across the south. He wouldn’t travel far.

Noble Yocum remembers it well. It was April 23, 1963. He was the Etowah County Coroner at the time.

Noble Yocum remembers it well. It was April 23, 1963. He was the Etowah County Coroner at the time.

“It was just past dark. Early evening hours,” Yocum said. He was at home when the phone rang. “I was called by the local sheriff’s office.”

A man had been found shot to death along U.S. Highway 11 in a rural, sparsely populated part of Etowah County.

“It was hard to believe. It really was hard to believe. But I went over there, to the scene. The body was still lying there in the road,” Yocum said.

The body was William Moore’s. Moore was a postal worker just shy of his 36th birthday and an unintentional civil rights martyr.

A Southerner by way of New York

Moore was born in Binghamton, New York, but considered himself a southerner because he spent part of his childhood on his grandparents farm in Mississippi. Mary Stanton wrote about Moore in the book Freedom Walk: Mississippi or Bust. She explains when he returned to New York he faced a harsh, snowy climate and a harsh, distant father.

“Bill grew up to be a bit of a loner, although he always had a great sense of humor,” Stanton said.

A high school teacher though did encourage his budding interest in philosophy and politics. Moore wanted to go to college. His father couldn’t stand the idea and flat out refused to pay for it.

So Moore joined the marines at the tail end of World War Two. He never saw combat, but used the G.I. Bill to go to college. He blossomed while studying in England, at the Sorbonne and in Madrid. After graduating he went to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Stanton said the bigger school and bigger city drove Moore to become a loner again.

Moore wanted to work in government or international relations. But his job applications weren’t going anywhere. His beloved high school teacher had died a few years before and the emotion of that experience welled up. In fact, Moore believed the teacher was still alive. Moore thought the reason his career was not gaining any traction was because the teacher was secretly maneuvering behind the scenes to help Moore to get the perfect job.

“Essentially he had a breakdown in Baltimore,” Stanton said. “And his father brought him back up [to New York] and he spent about three-and-a-half years in a mental institution.”

Stanton said Moore was diagnosed with schizophrenia, although he was never paranoid. He received the standard treatment of the day — shock treatment. Doctors wanted him to simply acknowledge that his teacher died which he eventually did. Then they released him.

“When he had the experience of being somebody on the fringes of society he was able to relate to other people who were for other reasons left on the margins of society,” Stanton said.

A Civil Rights Advocate

Moore began organizing self-help groups for former mental patients. He became involved in civil liberties causes. And he got married to a woman with three children whose first husband had been abusive.

“He was kind to her and she really needed somebody at that point in her life who was kind and she paid attention to him and was interested in what he was doing and at that point in his life that was a great gift to him,” Stanton said.

But their relationship fractured. Moore increasingly spent time on political causes, leaving the bills and the household to his wife. Also, he was an atheist. She was a devout Christian. He fought against prayer in public school. She wrote a letter-to-the-editor in the Binghamton newspaper distancing herself from his public professions.

William Moore worked as a letter carrier and transferred to Baltimore to be near the offices of the Congress of Racial Equality while his family stayed in New York. In the fall of 1962 he grew upset by Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett’s refusal to integrate Ole Miss. So Moore decided to write a letter to the governor denouncing segregation. And he, a postal worker would walk from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi to hand deliver the letter and discuss these issues man-to-man and southerner-to-southerner.

“He had this overblown sense that people could be reasoned with,” Stanton said. “He believed that people would do the right thing, if they knew what that was, if they could be convinced. And he was going to do that.”

Moore’s idealism and optimism caused friction with civil rights leaders in Baltimore. He once invited then Attorney General Robert Kennedy to an organization meeting believing civil rights workers had nothing to hide. They were not supportive of his letter idea either. Peace walks were a traditional protest tactic, but after all, this was the Deep South.

Robert Avery is a Gadsden City Councilman and was 14 years-old that spring.

Robert Avery is a Gadsden City Councilman and was 14 years-old that spring.

“It was a very intense climate at that point in time,” said Avery. He points out a mob firebombed a bus with Freedom Riders in Anniston two years before. Bombings were a regular occurrence in Birmingham.

“Eventually you knew it was coming. You just didn’t know when or how or what,” Avery said.

The March Begins

With two weeks vacation, William Moore walked out of Chattanooga on April 21, 1963. He wore sandwich board sign. One side read “Equal Rights for All (Mississippi or Bust).” He pulled a shopping cart for a suitcase and set out to reason with the Jim Crowe South.

Moore engaged with the periodic farmer or small-town waitress along the route. He offered copies of his letter while they warned him about how stupid and dangerous his venture was. He called newspapers and radio stations, trying to drum up publicity. But he wasn’t prepared for the physical demands. His feet grew calloused and bled. He was exhausted.

On the third day Moore stopped at a grocery store. Mary Stanton said he had a conversation about a poster in his shopping cart. It showed Jesus and read, “wanted – agitator, carpenter by trade, revolutionary, consorter with criminals and prostitutes.”

“They got into a long harangue about Christianity that made this grocer very angry,” Stanton said.

Moore left, but later that day the grocer drove by with a friend, to show him this stranger who didn’t believe in God. They argued again.

“It became more heated the second time,” Stanton said. “And that’s when Bill began to get rattled. He realized he was in a situation that could very quickly escalate. There was nobody else on the road for miles.”

But the men moved on. Word of Moore’s walk had spread by now. Two different law enforcement officers drove by, offering to give him a ride for safety, but Moore refused. It was getting late. So he stopped in a picnic grove along U.S. Highway 11 near Keener, Alabama. A few hours later, he was found dead.

But the men moved on. Word of Moore’s walk had spread by now. Two different law enforcement officers drove by, offering to give him a ride for safety, but Moore refused. It was getting late. So he stopped in a picnic grove along U.S. Highway 11 near Keener, Alabama. A few hours later, he was found dead.

A Shocking Murder

Former Etowah County Coroner Noble Yocum said when he got to the scene he found spent cartridges on the ground.

“After going through the man’s personal belongings I located a number where his wife was living up in Binghamton, New York. So not knowing where Binghamton, New York, was and not knowing anybody I called that lady collect,” Yocum said.

He said she was very calm. She knew her husband was taking a risk

“Next morning at 7 o’clock CBS News reported that I had called her collect during the night. Well, I had to. On a salary of $75 a month you don’t make many long distance calls,” Yocum chuckled.

Yocum says the murder shocked the community. He says race relations were good around Gadsden. With the national media coming to town it gave a bad picture of the south. Gadsden City Councilman Robert Avery sees another side of that coin. The national attention brought in numerous civil rights groups.

“Once they came into town, then that really kicked things off,” Avery explains. There were protests and organizing that spring and summer. Avery said Moore was the spark.

The murder was never officially solved. Suspicion fell on Floyd Simpson, the grocer who argued with Moore. Simpson’s rifle matched the bullets found on the scene. Witnesses saw his car on the highway near where Moore died. Simpson was a Klan member. He was arrested, but a grand jury refused to indict him. He died in 1998

Both Noble Yocum and Robert Avery agreed Simpson likely murdered Moore. Conventional wisdom suggests it was because of his views on integration. But author Mary Stanton believes Moore was killed because he was an atheist. Either way, it remains a cold case, a civil rights footnote filed away in the Etowah County Sheriff’s office.

Remembering Moore

Remembering Moore

William Moore’s name is etched in a black, granite disc as part of the civil rights memorial in Montgomery. Many names are written there. But his name is not on any marker or memorial in Etowah County.

Robert Avery is among those trying to change that. He said preliminary work has been done for a marker although they’re still looking for funding.

“It’s going to be out there on Highway 11 at the spot where he was shot and killed. That’s where we want to put it,” Avery said.

They just want to make sure William Moore is remembered.

~ Andrew Yeager, April 16, 2013

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

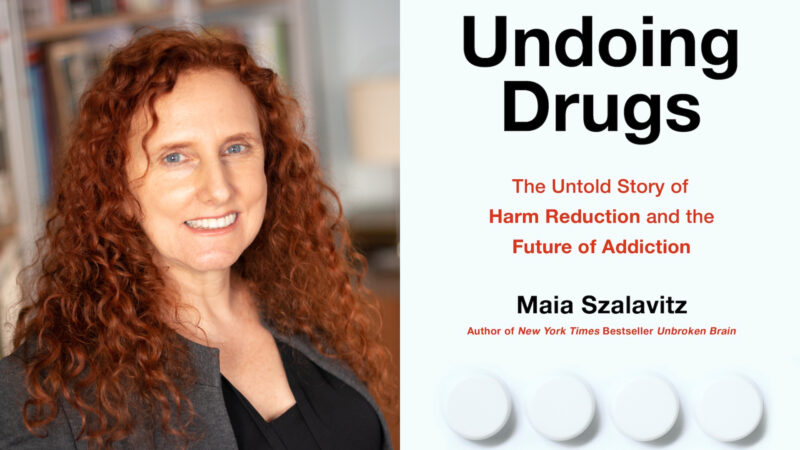

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.