Alabama Sales Tax on Food

With three children, Patty Hamme makes a lot of trips to the grocery store.

“I try to do like every two weeks a really big shopping which may take like an hour or hour-and-a-half. But I probably go to the grocery store every other day just for stuff.”

Hamme rummages through a kitchen drawer in her Alabaster home for a baking sheet. Her 11-year old son has settled on frozen pizza for lunch. She fixes a turkey sandwich with cheese and mustard for his twin brother. Those grocery bills add up. So too does Alabama’s 4% sales tax on food. Hamme thinks she spends about $600 a year in state sales tax for food. But would she notice if it were gone?

“Not a whole lot I don’t think. I’m just so used to paying it that it probably wouldn’t be that big of a huge change for me.”

Hamme keeps up the house and chauffeurs the kids. Her husband Curt runs a call center for a bank. It’s a different story for Dora Bonner and her family.

“Just scrapping by, just scrimping by.”

Silver-haired, black-rimmed glasses, Bonner sounds a bit exasperated. It’s understandable given this Birmingham grandmother has adopted her four grandchildren. Two teenage girls. Two younger boys. She says her social security check goes toward the bills. Her minimum wage job and food stamps have to stretch to cover the rest.

“I’m not wasteful. I buy just what I need. And still when I get home, I should have got some meal. I should have got some flour. It’s something you always need. Sugar or something. But you couldn’t get it then. You got to go back and get it again when you got a few more extra dollars.”

Bonner doesn’t know how much she spends on groceries, but she says she certainly could pick up a few extra items each shopping trip with those dollars now going to state coffers. And that’s the thing about the sales tax. It’s regressive. Those further up the economic ladder feel it less than those at the bottom.

“We are taxing low income people at a high percentage of their incomes and high income people at a low percentage of their income. And this bill will go a giant step toward making that a fairer system.”

Kimble Forrister is the State Coordinator of Alabama Arise, a coalition of religious and community groups which lobbies on poverty issues. The bill in the legislature would eliminate only the state sales tax on food, not taxes levied by county or local governments. It would also decrease the taxable income for all families in the state. Forrister says that’s good for low wage earners.

But the bill would also eliminate the state tax deduction for federal income taxes paid, which could hurt higher income earners.

“I have a real problem with this concept of giving with one hand and taking with another.”

Gary Palmer is the President of the Alabama Policy Institute, a free market, limited government think tank. He says he supports removing the state sales tax on groceries, but the current proposal isn’t the way to do it. He says it’s a piecemeal approach that offers short term gains for poorer Alabamians, but a long term loss. Palmer believes that if high-wage earners lose some disposable income, as they might with this bill, it’ll mean fewer jobs and opportunities for all Alabamians.

“We ought to be looking at what is in the best interest of Alabama economically because the best thing that we can do for low income people is put them in a position to get a job not try to help them out through the tax code.”

Palmer says he believes the plan actually raises income tax overall by $250 to $300 million. Proponents disagree, saying the measure is virtually revenue neutral. The bill’s sponsor, Democratic Representative John Knight of Montgomery says a family of four with a household income of $100,000 would end up paying $537 a year less in taxes. The savings would increase as household income decreases. Knight says only one in five Alabamians would not save money or break even. Critics say that number is actually closer to 30%. One thing is clear, the more mouths you have to feed, the greater the savings. That’s fine with Kimble Forrister of Alabama Arise.

“Whose gonna benefit from that? Families. Should we have a family friendly tax system? I think we should.”

Back at the Hamme resident, they estimate they’d break even. Maybe save a 100 bucks, Patty Hamme says.

“It wouldn’t bother me one way or another if we did it. But I think that it could be a very good thing for people who are in need.”

With just days left in the legislative session the bill’s passage is far from assured. The measure passed the House but is stalled in the Senate. If the Senate passes it, the proposal goes to a statewide vote in fall. Letting all voters weigh in, regardless of the length of their grocery list.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

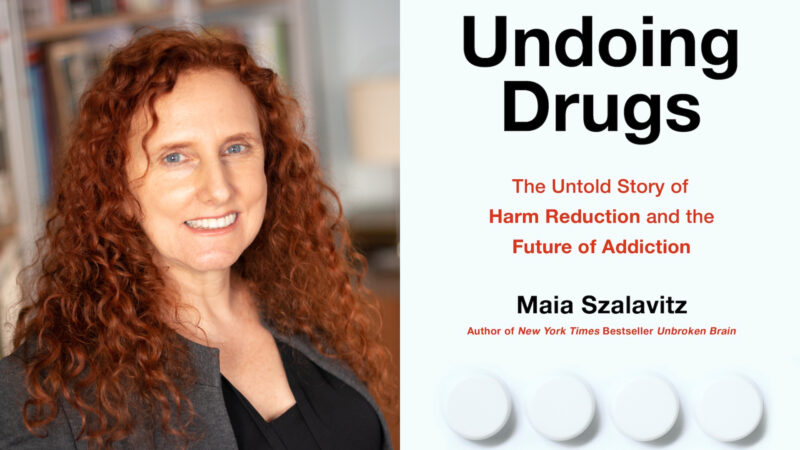

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.