SFS: Juvenile Crime

It’s 45 degrees on a late November morning. A group of high school-aged boys is assembled in rows on a sandy patch beside the parking lot of the Jefferson County Alternative School. They’re dressed in black sweatpants and sweatshirts. On the back of their sweatshirts is the word STAR. That’s the boot camp-type program to which these boys have been assigned. STAR is the last rung on the hierarchy of school disciplinary action, reserved for those who commit serious and repeated offenses.

Reggie Patrick, a 16-year-old high school freshman, went through the STAR program three times.

“I’d get suspended one day, come back, get suspended right back again. I was just never at school, couldn’t learn anything. I was always in trouble.”

In the seventh grade, Reggie was finally expelled.

He describes himself as nice and respectful and funny. But there is one character trait he returns to again and again:

“I could be mean. Real mean.”

By mean, Reggie is referring to his tendency to get into fights–fights that have on occasion turned bloody. One resulted in his arrest.

At that point, he didn’t envision much of a future for himself.

“I just thought I was gonna like, people always told me if you don’t finish school you’re gonna be on the streets or in jail, so I always thought I was gonna be in jail or something.”

But that was middle school. This year at Clay-Chalkville High School, Reggie is earning A’s and B’s. He’s on the basketball and football teams, and his peers nominated him Mr. Freshman. Reggie’s teachers say he’s made a complete turnaround. Many kids don’t.

“Because the data shows that once a child has that initial contact with the court system, the odds of them continuing to commit delinquent offenses increases. ”

That’s Jefferson County Family Court Judge Brian Huff.

“If these are issues that can be dealt with in the community, can be dealt with in the schools, can be dealt with in the home, that’s the ultimate goal.”

That’s the idea behind a new set of reforms to Alabama’s juvenile detention system. The Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative is being launched in four Alabama counties: Jefferson, Mobile, Montgomery and Tuscaloosa. Alabama is one of 21 states nationwide participating in the program funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. At other sites around the country, the program has helped to dramatically reduce the number of kids in detention, funneling non-violent offenders to community programs.

You would think this would be one area that’s fairly clear cut, whether a child goes to jail. But as it stands, that’s a very subjective call. Huff says that, too, would change, under the new initiative.

“Within the next several months, we hope to have what’s called a risk assessment instrument in place where it will take into account the child’s family, what other alternatives are out there, what is the offense, what is the child’s prior history, and the detention will be based on something scientific as opposed to some gut reaction.”

Huff says for the program to work, the entire community — from schools to churches to law enforcement — must work together to provide alternative modes of rehabilitation. Legal experts estimate about 80% of incarcerated children in Alabama have been locked up for non-violent offenses. It’s a stern consequence that comes at a high price: in 2006, Alabama spent more than $10 million to incarcerate children from Jefferson County in Department of Youth Services prisons. Ultimately, officials like Judge Huff hope fewer children will end up doing time.

“We’re not convinced that taking a child who’s non-violent, locking them up in jail, sending them off to some state-run institution is best serving the family, best serving the children. Most of the kids that I see in court have internal family issues. And if you don’t take that child, and take that family, and work with both of them, when the kid’s released from a state institution, he’s going back into the same environment, and odds are he’s gonna re-offend.”

The accommodations here at the G- Ross Bell Youth Detention Center in Jefferson County aren’t cushy by any standard. There’s a carpeted gymnasium, a drab lunchroom, and a cramped classroom containing desks jury-rigged from some old doors. Bill Lowe has been teaching at the detention center more than seven years. He says for some children, juvenile detention offers things that home cannot.

“We have actually had residents here who liked it here because they were provided with basic essentials–safety, food, shelter. Many of these young people don’t know when they go home if they’re gonna be safe, they don’t know if there’s gonna be something to eat, if there’s going to be electricity, …gang activity.”

It may be less restrictive for students, but going home at the end of each day can sometimes wipe out progress made during the school day. Billy Williams, the director of Jefferson County’s STAR program, notes this can be an issue at the alternative school.

“You’d be surprised at what some of them have to go home to. I’ve been over here spinning my wheels…Because that kid went home, now I’ve gotta start all over again the next day. Start all over again.”

Ideally, student misbehavior doesn’t escalate to the point of alternative school or juvenile detention. Schools are at the front line of juvenile crime prevention. School officials say simply monitoring students in school acts as a deterrent. Many in recent months have installed sophisticated surveillance systems that can pull up images with the click of a mouse.

At Hoover’s Spain Park High School, school resource officers Nina Monasky and Patrick Metcalf are hunched over a computer reviewing the surveillance tape from a health class. A girl had reported that someone stole her cell phone during that class. The incident happened to be captured on one of the school’s more than 300 surveillance cameras. It can be handy in instances like this. Still, officials are finding technology wields a double-edged sword in the world of juvenile crime. Police and school officials may be discovering new ways to use cameras and computers. But, as if often the case with technology, kids seem to stay one step ahead.

“Students are able to travel faster, they’re able to communicate faster and quicker, so if there’s any plan that’s being hatched, they’re much better able to execute that plan, illicit or licit, much faster than it used to be 10 or 15 yrs ago. Probably 10 or 15 yrs ago one would have had to go to a call box or telephone booth. Now they’re walking around with cell phones all the time.”

Aaron Moyana is the school safety and dropout prevention officer for Birmingham schools. He says social networking sites such as MySpace and Bebo have become breeding grounds for trouble.

“A lot of gang information, a lot of gang trafficking, a lot of fights are being promoted through those Web sites.”

With all of the changes and challenges in youth crime, the process of setting children straight can at times seem overwhelming. But Billy Williams, the head of the STAR program at the alternative school, tries to keep things in perspective.

He says he knows he can’t save them all, but if only one out of five children who come through this program become repeat offenders, he considers that a job well done.

Birmingham is 3rd worst in the Southeast for ozone pollution, new report says

The American Lung Association's "State of the Air" report shows some metro areas in the Gulf States continue to have poor air quality.

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

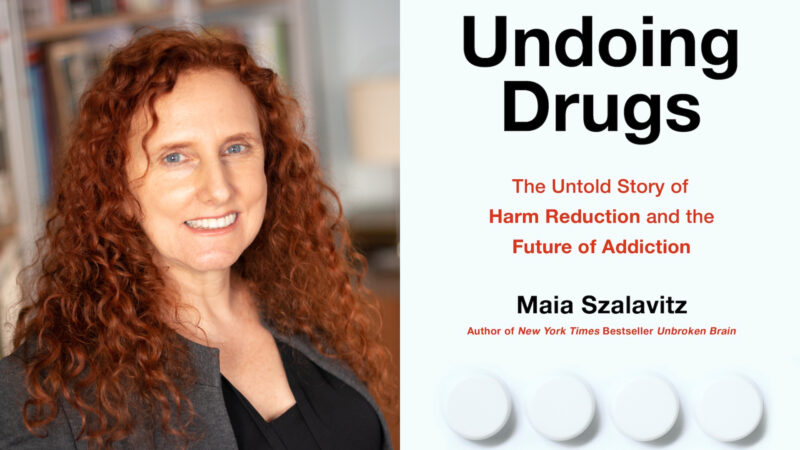

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.