Tutwiler Storytime

Normally, on a Saturday, the chapel at Julia Tutwiler Women’s Prison in Wetumpka would be empty and quiet. On this day, though, it sounds as like a hive of bees is inside. The brown and mustard room is awash in white uniformed women — but they’re not concerned with the spiritual, something much more down to earth has brought them here. Javon Robertson’s among those gathered in the room. She’s serving twenty years for first degree robbery and drug possession convictions. But she’s also a mother and almost since the day she walked through the door she’s been working to keep her relationship with her kids strong. “I have a seven-year-old and a five-year-old. Reading is really the most important thing you need to know in life and reading to them through Storybook it helps a lot, it’s good communication.” She’s talking about “The Storybook Project”, sponsored by the group Aid to Inmate Mothers, or AIM. The last Saturday of each month volunteers and AIM personnel meet at the prison, laden with books, tape recorders and cassettes. Once inside they help the mothers read books for their kids. Vicki Morrison is one of the volunteers. “You can tell that there’s just something missing for the women not being able to see their children grow and to be involved in their day to day activities.” Morrison says she thinks “The Storybook Project” plays an important role in keeping the women connected with their children and, apparently, so do the inmate mothers. AIM assistant director Larnetta Moncreif says the program often lets them reach out to their kids in a way they never have before. “For a lot of these women, most of them have never read to their children before so this, no only are they experiencing and maintaining that bond with their child, this is also allowing them to do something that they never were able to do before and that is read to their children.” Robertson adds it’s about more than just books. “They receive a tape and they get to hear your voice and I know that those kids can rewind and rewind and rewind that tape and they can hear your voice and they’ll probably say, ‘That’s my mama’s voice, that’s my mama’. Even with newborns, they can hear that and, you know, it’s amazing. There are over nine-hundred women in this population and over half of them comes and reads tapes, you know what I’m saying? And it’s just amazing.” The inmates come to the chapel in shifts throughout the morning. Books are spread across two tables at the front and spill over onto the alter itself. For some, it can be overwhelming to pick out just the right story. It takes Robertson about ten minutes to find a book she likes, then she finds a volunteer and settles down to read. A study, done by the University of Massachusetts in Boston, shows that programs like “The Storybook Project” are vital to female inmates and their children. Inmate moms are three times more likely than inmate dads to have been the primary caregiver for their kids. The study says having mom locked up stresses kids out. The kids of inmate mothers who don’t hear from their moms tend to develop behavioral problems and can often locked up themselves. AIM’s Larnetta Moncreif says that’s one reason “The Storybook Project” began eight years ago, to help keep the kids of inmate mothers out of trouble by keeping mom in their lives. And she says it’s allowed many mother’s who didn’t really know their kids to finally connect with them. “For some of these women that I’ve talked to, some of them never had a relationship with their children, for whatever reason it was. This, if you never did have a relationship with your children, you can start now. And for those that had a relationship, it strengthens the bond or it allows you to continue to have that relationship with your children.” AIM is doing more than just letting moms read to their kids. They also bring the children to see their moms once a month. Those visits and books have meant a lot to Javon Robertson’s kids. Their grandmother says they kids eagerly await the arrival of their new book each month — almost as much as their mother looks forward to reading them. “I love you, I’m looking forward to coming home with you all. Be good and I’ll see y’all soon.” Robertson’s sure she’ll be seeing her children on the outside soon. She says she’s worked hard to better herself since her incarceration. She’s not part of Tutwiler’s work release program and is confident she’ll be paroled when she’s up for review in March of 2007. “I mean, I just know it’s a change in me, from my image, my whole demeanor, the outside. I mean, I don’t even look like the same person no more. I mean I pray and I’m God-fearing today. You know, there’s just not a doubt in my mind that when I leave from here I can leave and be all I can be, with my kids.” Until then she’ll continue sending her kids books every month.

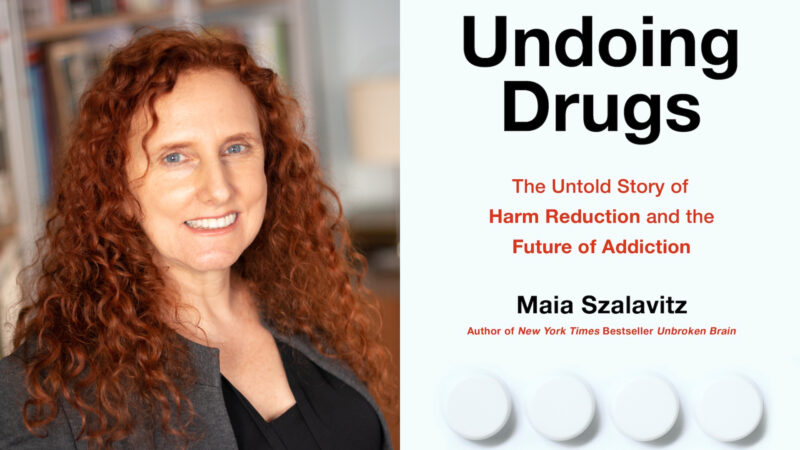

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What’s your favorite thing about Alabama?

That's the question we put to those at our recent News and Brews community pop-ups at Hop City and Saturn in Birmingham.

Q&A: A former New Orleans police chief says it’s time the U.S. changes its marijuana policy

Ronal Serpas is one of 32 law enforcement leaders who signed a letter sent to President Biden in support of moving marijuana to a Schedule III drug.