Highway Tango

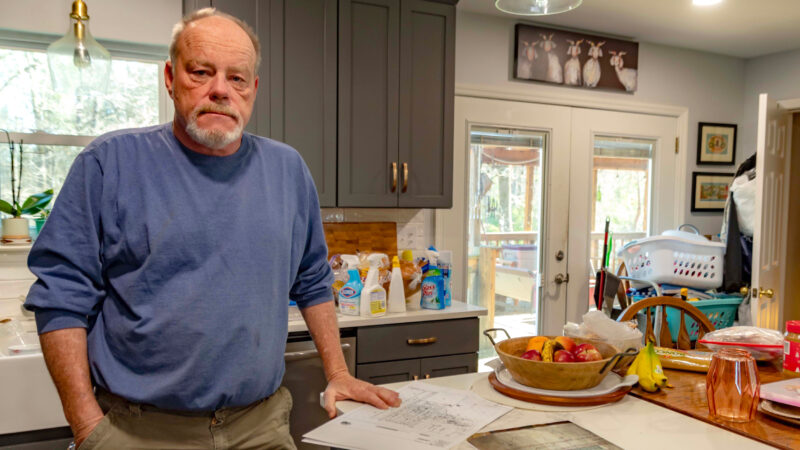

Most of the time it’s cordial – a turn signal and you’re allowed to pass,

a wave on the steering wheel telling the other guy it’s OK to get in front or even flicking the lights on and off to say thank you for the nice gesture.

But sometimes, the meeting isn’t so nice.

“(Just) riding down the interstate with the grill of a truck six inches from your face…it’s not real fun.”

That’s David; he didn’t want to give his full name because he’s been in the driver’s seat of both kinds of vehicles, sitting atop four wheels and, a few years ago, atop eighteen.

He says his experience on I-20 a few months back opened his eyes to the dangers of the convergence of big trucks and cars on Alabama highways.

“About 5:40 in the morning, I was passing the Chula Vista exit, passed a truck in the left lane, merged back into the right lane, there was another truck in the left lane, I was passing it in the right lane. About the time I got my rear wheel to its front wheel, the driver decided he wanted to be in the right lane, so he decided to merge, clipped the back end of my car, where he slammed my driver’s side door into his grill.

As a former commercial driver, David says he sympathizes with the truckers and remembers the long hours and pesky cars that used to zip in and out of his way. But he says there’s no excuse for what he calls a lack of enforcement – of cars and trucks – on Alabama highways.

“The state trooper… Now I was in St. Clair County, he had to come from Shelby County. They had to wake him up, so he had to get in his car in Shelby County and come. We had to wait almost an hour and fifteen minutes for him to get there. I mean, there was no other state trooper anywhere closer than an hour and fifteen minutes that could’ve serviced that accident?”

No, there wasn’t. Because on average, there are only about half-a-dozen state troopers who are on the roads after midnight.

“Truckers know this… they know everything; they’re in communication with each other. They know where trucks are being inspected. There are other routes; they take those. It’s sort of an endless game, but it’s not a game; it’s very dangerous.”

Ginny MacDonald writes a popular column called “Driver’s Side” for The Birmingham News. She says readers bring up the issue of truck safety time and time again.

“In the column, we get about 15 submittals a week. And I would say ranking third in that is the absolute fear of trucks. Of being out there, of complaints, of people saying why do they tailgate us, why do they go so fast?”

“I think the idea is that we don’t have the facilities, we don’t have the personnel. And it’s much easier to escape attention in Alabama because of that.”

State trooper Captain Harry Kearley oversees the state of Alabama’s truck inspections unit for the Department of Public Safety.

“(If your) daddy’s watching you, you don’t misbehave. Because you know you’ll get caught and get in trouble. Well, the same thing applies. If we don’t have the proper personnel and adequate personnel to monitor this driving behavior, then they’re pretty much going to drive the way they want to. Absent any interference from us, they’ll do like they please.”

And that means hammering it – you know, pedal-to-the-medal – or making abrupt lane changes and following too closely. Those actions that a Triple A Foundation study found to be most closely associated with fatal highway accidents.

But the study, released in 2002, shows that in a majority of car-truck crashes, car driver error is to blame.

Mike Russell is a spokesman for the American Trucking Associations.

“We’re not throwing blame, but that shows that the root – or the largest part of the problem – is human behavior and that’s where we think we need to focus most of our efforts… on the human factor: on correcting and training drivers to share the road safely.”

The Triple A Foundation study showed that car drivers are maneuvering around big trucks like they would around any car. Problem is, Russell says, an eighteen wheeler that weighs tons more than a car can’t stop in the same distance as your smaller Ford or Chevy.

“It takes a truck traveling at a normal rate of speed about the length of a football field to come to a safe stop.”

He says his organization goes on the road to teach car drivers how to drive around big trucks.

And truckers agree, more should be done to highlight the disconnect.

“I wish they had more instructional videos or, you know, just some commercials. Come out there once in a while and show them what happens when a car meets up with a big truck.”

Sef Gonzales runs a trucking route out of Missouri and comes through Birmingham on a frequent basis. He says congestion in the Magic City is his biggest pet peeve, but he says the worst problem is that car drivers forget who they’re dealing with.

“I mean, I don’t want to tangle with no train, cause a train’s gonna beat me. A car should have the same consideration. I mean as far as respect, you know. They gotta watch out for this truck and be careful and mind themselves around the truckers. Sometimes the trucks can’t see them you know, or they get in this position where they put themselves in harm’s way.”

Larry Hall agrees. He’s running a route to Atlanta hauling paper supplies.

“I see cars, pretty regularly, go from the left lane all the way over to the right (snap) I mean like that and I mean they’ll go right in front of you, to get off on their exit that they almost just missed. Or they’ll jump off in front of you and slam on their brake – well, not slam on their brake – but stop real, or slow down real quick.

But car drivers who are on the road frequently say there should be different rules for big trucks. If cars should have to drive differently around trucks, then trucks should be held to a higher – or a safer – standard.

At least ten other states have lower speed limits (for trucks) and many other states have mandatory lanes for trucks.

Brian Swinford is a pool supply representative who does a lot of traveling on the interstates across the Southeast…

When you’re talking about something that weighs significantly more than a car, is less responsive than a car is and one object alone that could cause damage to several vehicles pretty easily, I think you’ve got to put some extra onus on the larger trucks.”

He says the larger the truck, the worse the disaster if something goes wrong – no matter who’s at fault.

“Well, yeah, I mean especially when you’ve got a truck that’s overweight or has been improperly loaded so that it doesn’t have a balanced load and the guy has to make any sort of sudden emergency movement. Obviously, you’re looking at a big risk there. I don’t want that coming up behind me and not knowing if he can’t stop. Or if he does try to stop that his load shift he’s going to be all over the road. It’s just, it’s scary.”

That’s where inspection posts – weigh stations – are helpful. Highway officials such as Randy Braden of the Alabama Department of Transportation say they assist psychologically in proving to truckers – and even car drivers – that there is enforcement of not only their loads, but of their actions.

“If he sees a weigh station out there and you got stations out there, he’s not only going to look at his weight, he’s going to think about safety, his hours of service…”

(Recorded at weigh station) This facility off I-20 near the Georgia line is one of the most state of the art in the nation – able to weigh trucks while maintaining low speed, fully inspect rigs that are overweight or look dangerous and write citations to those trucks that don’t comply with the law.

But while high-tech and busy when it’s open, it is the only weigh station in the state of Alabama.

State officials say it was originally built during Governor Fob James’s administration to catch fuel tax violators coming across the state line from Georgia – where gasoline was cheaper.

Since then, Braden says ALDOT’s contemplated building others, at least three more on other freeways in and out of the state. But, like everything else, it costs a lot of money.

“They’re anywhere from five to seven million dollars. You’re competing for that money. Do you want to resurface a road, you want to build new roads or do you want to build a weigh station?”

Neighboring states have found the money to build such stations. In Mississippi – a state with about half the population of Alabama – there are 32 fixed stations. In Florida, 20. Georgia has 19 and Tennessee has 10.

But Braden says the fact that there are so many stations across state lines actually played into Alabama’s plans.

“See the theory that Alabama had – and this is the reason we don’t have more weigh stations was the theory was truckers coming through the southeast if they were overwieight or they were speeding or they had safety violations or hours of service violations, we have every state around us with weigh stations. So the theory was that if they were OK in the other states, then they’re OK to come through Alabama. (What if other states thought the same way?) Well they don’t. And that’s good. That was the theory. I’m not saying it’s right or wrong, that was the theory why Alabama doesn’t have them.”

Braden says despite the fact there’s only one inspection station, there is quite the robust inspection process. There are 14 specialized inspection devices such as weigh-in-motion or WIM pads that are planted beneath highways statewide that can accurately determine if a truck’s load is overweight. There are at least two dozen roving federal motor carrier inspection teams and 15 state troopers with ALDOT inspectors watching for unsafe trucks.

“Anything we can do to indicate to the industry that we are aggressively enforcing the safety regulations and aggressively attempting to gain compliance in the regulations would certainly help us out.”

State trooper Captain Harry Kearley says it is a perennial problem. Every year, his department – the Department of Public Safety – has to compete from money with everything from Medicaid to prisons.

It is a lot of competition. But Alabama drivers are the ones who are losing.

According to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, the state of Alabama ranked second in the nation in 2003 in the number of fatal car-truck accidents. And of the ten states with the worst numbers, only Alabama and Missouri rank outside the top ten in population. That means there are fewer people on the roads, yet more people are dying in those crashes.

Less enforcement. More renegade drivers. More accidents and deaths. It’s what the newspaper columnist Ginny MacDonald reads in her inbox and mailbox everyday.

“That’s why it’s called ‘The Hammer State.’ Wide open all the way through.”

The accident victim David says he remembers what his old trucking buddies used to say…

“They always used to talk about Alabama being like the slalom course: get on it, go through as fast as you can, get to the other side, slow down.”

Drivers of cars and trucks live in different worlds. A world of different sizes, different priorities.

For people who can understand both sides of the debate – and, in David’s case, who’ve experienced the wrong side of a truck – it’s frustrating they say that there isn’t more emphasis put on trucking safety, when most other states do more, pass more laws, commit more money.

“I know the state would like to do something better they just don’t seem to do anything better.”

“For his part Governor Riley has made a commitment to get more troopers on the road, at least 200 more in the next two years. And he’s enlisted sheriff’s deputies from all 67 counties to help reduce speeding on Alabama highways.

Everyone seems to agree that on the road, drivers – whether they be in a truck or a car – are much more likely to obey the rules and be safe when they know they’re being watched and laws are being enforced.

In Alabama, the watching costs money. And enforcement is dicey because there’s so little of it.

Drivers – no matter what they’re hauling: paper or kids – are less safe because of it.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What’s your favorite thing about Alabama?

That's the question we put to those at our recent News and Brews community pop-ups at Hop City and Saturn in Birmingham.

Q&A: A former New Orleans police chief says it’s time the U.S. changes its marijuana policy

Ronal Serpas is one of 32 law enforcement leaders who signed a letter sent to President Biden in support of moving marijuana to a Schedule III drug.

How food stamps could play a key role in fixing Jackson’s broken water system

JXN Water's affordability plan aims to raise much-needed revenue while offering discounts to customers in need, but it is currently tied up in court.

Alabama mine cited for federal safety violations since home explosion led to grandfather’s death, grandson’s injuries

Following a home explosion that killed one and critically injured another, residents want to know more about the mine under their community. So far, their questions have largely gone unanswered.

Crawfish prices are finally dropping, but farmers and fishers are still struggling

Last year’s devastating drought in Louisiana killed off large crops of crawfish, leading to a tough season for farmers, fishers and seafood lovers.