Food Safety

“I eat ground turkey. I make ground turkey balls, turkey meat loaf. I even tried making a turkey hamburger the other day! (laughs) because I missed eating hamburgers.”

Teat and many of her friends in McCalla, Alabama, stopped eating beef after Teat’s husband – Jim – died three years ago. His autopsy blamed a subdermal hematoma, but Teat swears Jim died of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease – or CJD… the human version of Mad Cow disease. He was an active 74 year old who loved to garden and exercise on his rowing machine when he fell ill.

“He kept falling and his arm kept jerking and we were eating lunch, it was on a Saturday, and his arm just started jerking every second and his face fell over in his plate.”

Eight months after the first symptoms appeared, Jim Teat was dead.

The U.S. government says the risk of contracting CJD is very small. The Centers for Disease Control reports just one CJD death per million population each year – and certain forms of CJD may occur naturally in older people. A variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob, which researchers suspect may be caused by eating meat from infected cows, has killed 153 people, mostly in Britain. But the recent discovery of an infected cow in Washington State has focused a lot of attention on the U.S. beef industry.

In Trussville, Alabama – rancher Richard Beard tends to his herd of 300 cattle. He’s been in the cattle business more than 50 years. The past few years he’s raised all-natural beef – no antibiotics or hormones.

“As far as I’m concerned, American beef – regardless of whether it came from this farm or some farm in Texas or Kansas, it’s all safe because it’s been raised under safe conditions.”

Safe conditions including a 1997 USDA ruling that banned feeding animal by-products to cattle. Mad cow – also known as bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE – is spread by animal feed contaminated by brain and spinal tissue from infected cows. The Washington State cow that tested positive ate contaminated feed before Canada and the U-S enacted the ban. Nearly any beef you’d buy at the supermarket now would have been born after the ban.

Just up the road from Beard’s ranch, large animal veterinarian David Evans inspects cattle getting ready for auction at the Asheville Stockyard. Evans says the threat of mad cow infection in humans has been blown out of proportion. It’s a legitimate concern for the cattle industry from an economic standpoint – one outbreak and beef sales drop and the export market dries up – but, Evan says, a new cattle tracking system that’ll be mandatory starting this fall should help put those fears to rest.

“We’ll be able to identify the animals from birth to the feed lot and consumers will know where they came from and what country or origin they originated in.”

“Mad cow is glamorous. It gets a lot of press.”

Jay Franks is president of SafetyCheck America – a Chicago-based consulting firm that helps food companies comply with federal regulations.

“The real risks are everyday salmonella, e-coli, listeria, the things that our company deals with on a day-in, day-our basis.”

The science backs him up on that. Each year in the U.S. 50 people die of campylobacter – a bacteria spread through contaminated poultry and unpasteurized milk. 60 die from e-coli. Listeria kills 500 Americans annually and Salmonella? 600 deaths each year in the U.S.

In the food safety lab at Auburn University – researchers are working on technology that may one day protect consumers from these and other potentially deadly foodbourne illnesses.

There’s a machine here called the stomacher. It’s about the size of a bread box, with two paddles that beat on a plastic bag filled with a water-like buffer and 25 grams of a meat sample. Once the meat is mixed into the buffer the sample is tested for e-coli, salmonella and other contaminants. Dr. Jean Weese and her colleagues are also working on a microchip that could be implanted in the soaker pad at the bottom of a meat package to detect bacteria.

“And then when you scan it over the scanner at the grocery store an alarm light would go off – this has bacteria – don’t sell it!”

Weese imagines a day when consumers could have their own hand-held scanners at home to check meat for contamination. It would increase food safety, she says – but at what cost?

“The only people that are buying into it are the chip people because they can see ‘wow, every package of chicken, this is dollars! Cha-ching!’ you know. But the food industry is saying, ‘Wait a minute! We’re not going to be able to sell any product! This is going to be a disaster for us!’”

Weese worries that increased pressure from government regulators and consumers for food that’s 100% percent safe will mean that eventually, consumers won’t be able to buy raw product in the grocery store. Everything – including fruits and vegetables, which can harbor e-coli and other bacteria – will be pre-cooked, pre-packaged… and probably more expensive!

Will shoppers go for it? Reaction is mixed at the Piggly Wiggly Grocery Store in Homewood. Aubrey Henderson says she already takes enough precautions at home – she’s not worried about the safety of her food.

“I wash my fruit before I use it – apples and lemons and oranges, things like that. I clean my vegetables real good.”

June Farrell also washes her fruits and veggies and takes care to cook her meat thoroughly, but still – she worries. And so does shopper Truman Parrott.

(Farrell) “Well some of this stuff they’re putting in the cows I don’t agree with anymore. Even these chickens – I was just reading to see what was in them.”

(Parrott) “When it’s on the television and it first comes out and everything it’ll kind of worry you and you’ll think about it awhile, but after a while you have to go back to living and you just have to eat something and hope that it won’t kill you.”

Americans love food – it’s a pillar of our economy, it even has its own cable TV channel. But we get really anxious when we think that our food could hurt us – make us sick, make us fat, or even kill us. So, we’re bound to continue the public dialogue about the pleasures and perils of our breakfast, lunch and dinner.

— causes more than 2 million infections annually in the U.S.

— approx. 50 deaths annually

— from contaminated chicken and unpasteurized milk

— may be drug resistant

— nearly 1.4 million cases of illness annually

— estimated to cause 600 deaths each year in the U.S.

— from contaminated beef, poulty, pork and eggs. Experts say more than half of all chicken on grocery store shelves may contain salmonella.

— may be multi-drug resistant

— approx. 73,000 cases annually in the U.S.

— more than 60 deaths each year

— acquired primarily through ground beef, but can be present on lettuce, unpasteurized milk and juice, and contaminated water.

— only a problem when transferred from the intestines (where it is common) to other parts of the body

— causes 10,000 urinary tract, 25,000 systemic blood, 40,000 wound, and 1,100 heart valve infections each year in the U.S.

— nearly 500,000 annually in the U.S.

— about 3% of people infected with one kind of Shigella will later develop Reiter’s Syndrome, which can lead to chronic arthritis

— acquired by consuming contaminated food or water or swimming in water contaminated with human or animal waste

— 2,500 cases annually in the U.S.

— 500 deaths each year, mostly pregnant women, newborn children and people with weakened immune systems

— responds to antibiotics, if administered promptly

— Listeria food poisoning is mainly a problem with ready-to-eat foods

Why haven’t Kansas and Alabama — among other holdouts — expanded access to Medicaid?

Only 10 states have not joined the federal program that expands Medicaid to people who are still in the "coverage gap" for health care

Once praised, settlement to help sickened BP oil spill workers leaves most with nearly nothing

Thousands of ordinary people who helped clean up after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico say they got sick. A court settlement was supposed to help compensate them, but it hasn’t turned out as expected.

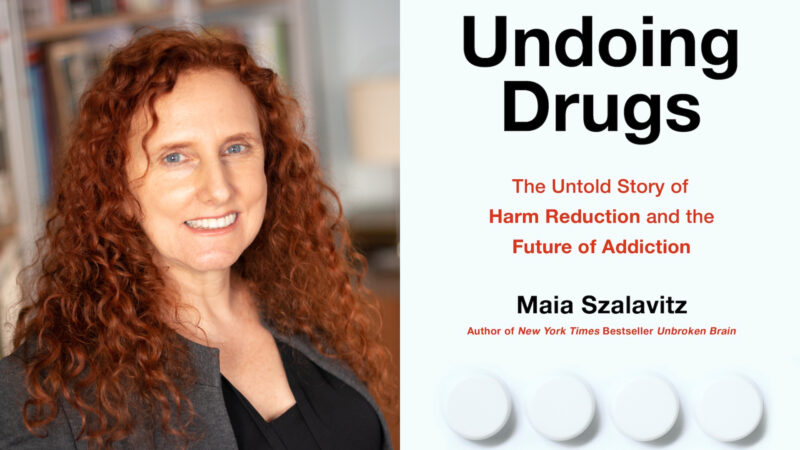

Q&A: How harm reduction can help mitigate the opioid crisis

Maia Szalavitz discusses harm reduction's effectiveness against drug addiction, how punitive policies can hurt people who need pain medication and more.

The Gulf States Newsroom is hiring a Community Engagement Producer

The Gulf States Newsroom is seeking a curious, creative and collaborative professional to work with our regional team to build up engaged journalism efforts.

Gambling bills face uncertain future in the Alabama legislature

This year looked to be different for lottery and gambling legislation, which has fallen short for years in the Alabama legislature. But this week, with only a handful of meeting days left, competing House and Senate proposals were sent to a conference committee to work out differences.

Alabama’s racial, ethnic health disparities are ‘more severe’ than other states, report says

Data from the Commonwealth Fund show that the quality of care people receive and their health outcomes worsened because of the COVID-19 pandemic.